WWI in Color

“When the World Turned to Color ” — 20th exhibition of Šechtl & Voseček Museum of Photography.

-

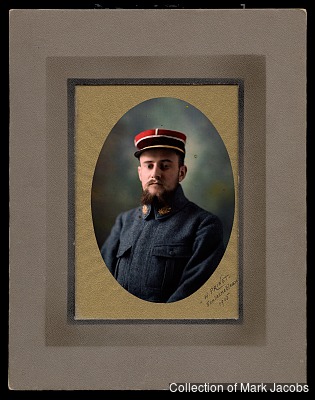

“Fontainebleau, 1915”.

H. Prinet

Autochrome,

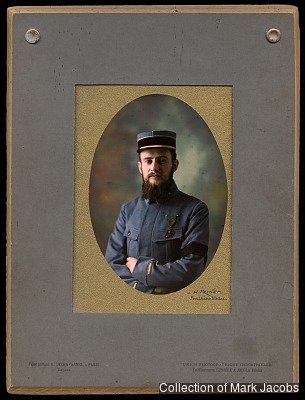

Owner of the original autochrome: Collection of Mark Jacobs All rights reserved, use of the digital reproduction is possible only with written permission from the owner of photographThese two portraits are of the same soldier, a Second Lieutenant, done at different points in time. The first is dated to 1915, the second one is undated though obviously some time has elapsed, perhaps several years, since the first portrait was made. The war has etched itself on the unknown soldier’s face. In the first portrait, the Second Lieutenant appears confident, perhaps a little too well-fed, pudgy even. No ribbon or medals decorate his chest. In the second portrait he appears to be thinner and perhaps a little less sure though he certainly remains proud. Now a veteran of the Great War, he wears the Croix de guerre and a black arm band. Both Autochromes are in “A. Lumière & Ses Fils” cardboard passe-partout with R. Dechavannes, Paris, Depose (registration mark for the passe-partout itself). However, such mounts do not denote that Lumière was the photographer, only that they manufactured the mount.

-

French Soldier.

H. Prinet

Autochrome,

Owner of the original autochrome: Collection of Mark Jacobs All rights reserved, use of the digital reproduction is possible only with written permission from the owner of photograph

-

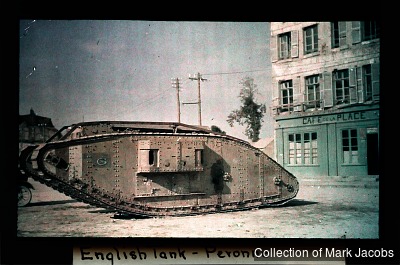

“English Tank—Peronne”.

The American Committee for Devastated France

Autochrome 5 × 4 inches,

Owner of the original autochrome: Collection of Mark Jacobs All rights reserved, use of the digital reproduction is possible only with written permission from the owner of photographThe American Committee for Devastated France (1917 – 1924) was one of many relief organizations—often founded and staffed by women—that sprang up in the United States during the First World War. The group was relatively small (some 350 women of a total of 25,000 who served abroad during the war), but the effects of their commitment were profound. The committee was led by Anne Morgan (1873 – 1952), a daughter of the financier J. Pierpont Morgan. As she rallied potential volunteers and donors on speaking tours across the United States, Morgan harnessed the power of documentary photography, in both black and white as well as in color, to foster a humanitarian response to the plight of French refugees. As Anne Morgan noted in a letter to her mother in 1918, “People at home seem to care more about photos than anything else, as nothing that one tells them is able to give them the real picture.” Though many Autochromes exist showing the devastation caused by the First World War, they are almost always French in origin. Currently, these are the only known American examples.

-

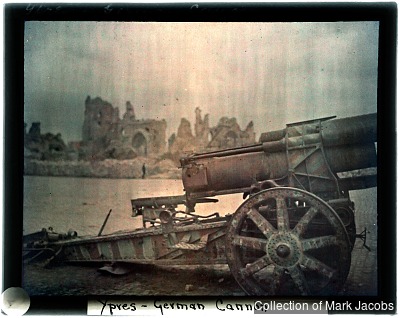

“Ypres—German Cannon”.

The American Committee for Devastated France

Autochrome 5 × 4 inches,

Owner of the original autochrome: Collection of Mark Jacobs All rights reserved, use of the digital reproduction is possible only with written permission from the owner of photographWhen the first American volunteers arrived in northeastern France in 1917, they witnessed destruction on an astonishing scale. Several years of war had decimated the countryside. “You can drive going forward in a straight line for fifteen hours and see nothing but ruins,” Anne Murray Dike, the co-founder of the committee explained in 1919. People had lost nearly everything—not only their homes and livelihoods but a whole generation of young men. The committee commissioned photographs of the devastation. Full-page images ran in American newspapers, exhibitions were mounted, and sets of prints were sold for three dollars a dozen. The photographs conveyed to Americans the enormous need for relief in the form of monetary support, donations in kind, and volunteerism.

-

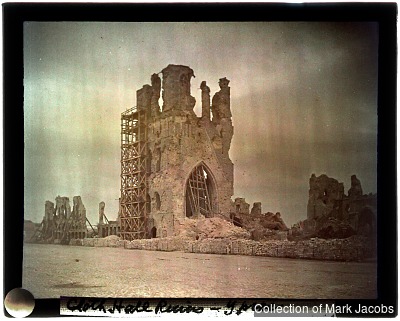

“Cloth Hall Ruins—Ypres”.

The American Committee for Devastated France

Autochrome 5 × 4 inches,

Owner of the original autochrome: Collection of Mark Jacobs All rights reserved, use of the digital reproduction is possible only with written permission from the owner of photograph

-

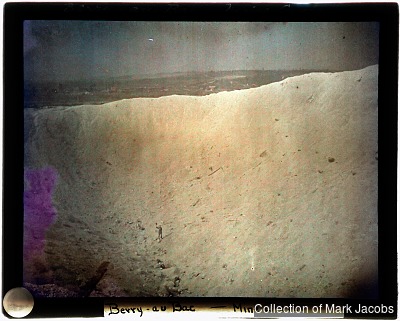

“Berry-au-Bac; Mine Crater”.

The American Committee for Devastated France

Autochrome 5 × 4 inches,

Owner of the original autochrome: Collection of Mark Jacobs All rights reserved, use of the digital reproduction is possible only with written permission from the owner of photograph

-

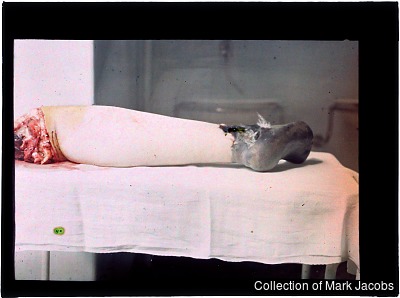

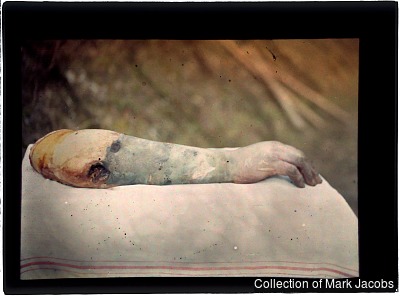

“Gangrene”.

Émile Chautemps (–)

Autochrome 9 × 12 cm,

Owner of the original autochrome: Collection of Mark Jacobs All rights reserved, use of the digital reproduction is possible only with written permission from the owner of photographÉmile Chautemps was both a doctor and a politician. He was the mayor of Tours and a chief medical officer of the military hospital in that city during the First World War. He was the brother of Camille Chautemps, the French President who was convicted, in absentia, of collaborating with the Vichy government after the Second World War.

It seems somewhat incongruous to have used what many consider to be the most beautiful of color processes to make such gruesome and horrifying images. However, Autochromes offered two advantages: they provided a realistic image of the condition in question and moreover they were easy to transport and display. In such a way physicians were able to document and share their latest treatment options to their peers. Chautemps photographed the wounded, soldiers burned by the gas, and dissected autopsied bodies. These scientific documents are among the first in the long litany of suffering from twentieth century conflicts. Despite their hardness, these pictures remind one of the aspect of war that should not be forgotten.

-

Amputation.

Émile Chautemps (–)

Autochrome 9 × 12 cm,

Owner of the original autochrome: Collection of Mark Jacobs All rights reserved, use of the digital reproduction is possible only with written permission from the owner of photograph

-

Soldiers Washing Clothes.

Albert Samama-Chikli (–)

Autochrome 13 × 18 cm,

Owner of the original autochrome: Collection of Mark Jacobs All rights reserved, use of the digital reproduction is possible only with written permission from the owner of photographAlbert Samama-Chikli, organized the first screenings of Lumière films in a Tunis shop in 1897. A truly remarkable individual, Chikli is also credited with introducing the first bicycle, telegraph and X-ray machine to Tunisia. However, he retained his interest in film and actually became a filmmaker in both Tunisia and France. During the WWI, Chikli filmed the French Army at Verdun in addition to his work with autochromes. The plate reproduced here was taken by Chikli in early 1916 in Tunisia. It depicts an ordinary yet an absolutely necessary activity during wartime, washing cloths. French soldiers in the colonies during the war were given khaki uniforms as previously worn by the British. Native soldiers chose to wear the uniform of the zouave, based on national folk costumes of elements in the Maghreb countries (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia).

-

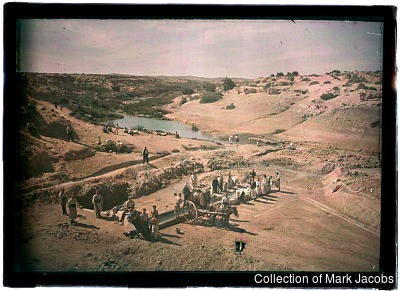

Photographer Unknown, Three French Artillery Officers.

Photographer Unknown

Autochrome 9 × 12 cm,

Owner of the original autochrome: Collection of Mark Jacobs All rights reserved, use of the digital reproduction is possible only with written permission from the owner of photographAt around the same time Chikli was photographing in Tunisia, an anonymous photographer, probably another soldier, photographed three French artillery officers staring pensively down upon a small river somewhere in France. Early in the war, French Soldiers wore a red stripe on their uniforms. However, red proved to be an irresistible target for German sharpshooters and the red stripe was soon retired.