Josef Jindřich Šechtla and Leica camera

Ninth exhibition of Šechtl & Voseček Museum of Photography.

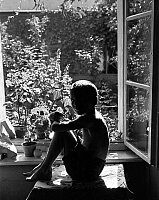

The Leica I, the first camera built to use 35mm film (originally developed as movie film), was introduced in 1925. Because of its small size and excellent optics, it was an immediate success. "Small negatives—large images" was the slogan of Oskar Barnack, designer of the camera which was soon to change the world of photography. The small camera quickly developed a new style of photography, where people could be photographed on the streets, without them being aware.

Exhibited photographs

This exhibition was prepared to celebrate the completion of our project of digitizing all 300 rolls of 35mm film preserved from the work of Josef Jindřich Šechtl. It shows a selection from his Leica work. We have chosen 30 photo essays, and have displayed several photographs from each. The complete photo essays can be found in our digital archive.

- 1928

Exhibition of Professional Photographers in Brno- 1928, 1929

Christmas; From Bálkova Lhota to Pejšova Lhota by car- 1930–35

Drill of the František Palacký 11th Infantry Regiment- 1931

“Pupa first time at school, for school, from school, away from school”- 1931, 1932

Sokol swimming baths- 1932

Farmers’ Militia

Antonín Čermák, mayor of Chicago in Tábor- 1933

“Soccer from Rome, see also Ferenc Futurista”- 1932–35

Škoda car workshop on Vančurova Street- 1934

Cardinal Karel Kašpar in Pelhřimov

Beauty of Miličín- 1934–35

48th Regiment stuffing straw mattresses, Pelhřimov- 1935–36

Army music band, Pelhřimov

Trip with Milena and Cízlerová- 1936

Dresden

Berlin during the 1936 Olympic Games

Funeral of city mayor of Mladá Vožice Rudolf Žahour- 1938

Re-opening of railroad from Tábor to Bechyně, with František Křižík

3rd meeting of Jawa club

Xth Sokol meet (“Slet”) in Prague

President of Czechoslovakia, Edvard Beneš in Tábor- 1938–41

Building new hospital- 1938–39, 1944

Building Church of God's Warriors; Celebration of Czecho-Moravian Church- 1939–45

Signs of Occupation in Tábor

Exercises of Curatorium in Tábor- 1945

End of World War II- 1947

Orphanage in Kyselka- 1948

Reunion of WWII prisoners

Exhibition of posters

May 1st celebration

Funeral of President Edvard Beneš- 1948–54

Farmers at Grand Hotel- 1950

Apartment of actor Jaroslav Hurt in Tábor

Rebuilding Karolín

Photographs from opening day

Leica (Leitz Camera)

The Leica I (Pic 2), the first practical camera built to use 35 mm film (originally developed as movie film), was introduced in 1925. Because of its small size, excellent optics, reliable design and the easy availability of film, the new camera was an immediate success. “Small negatives — large images” was the slogan of Oskar Barnack, designer of the camera which was soon to change the world of photography.

While the technical quality of photographs taken on 35 mm film wasn’t comparable with that of photographs taken by cameras with large glass plate negatives (such as 13×18 cm), the small camera was readily available, inconspicuous, and the shots were reasonably cheap. It quickly brought about a new style of photography, where the photographer could take photographs of people on the streets without them being aware.

Josef Jindřich Šechtl and Leica

Josef Jindřich Šechtl (1877 – 1954) proprietor of the important Šechtl & Voseček portrait and photographic studio in Tábor, was also a passionate photo-journalist and documentary photographer. He first tried using the Leica while attending the first National Exhibition of Professional Photographers in Brno in 1928, and our oldest dated 35 mm film is from this exhibition. The camera he subsequently used is believed to have been bought for him as a Christmas present, for Christmas 1928. This made him one of the pioneers of 35 mm photography in Czechoslovakia. He used his Leica I camera, later upgraded to a Leica II, daily until his death in 1953. During this time, he photographed in great detail the events of the 1930s—a time of spreading industrialization, especially in the automobile industry, but also of financial crisis; World War II; and post-World War II, including the communist takeover in 1948. Partly through good fortune, and partly because of its small physical size, the whole archive was preserved in a family sideboard, without having been subject to any censorship.

Digitizing the archive

Our project of digitizing the archive of negatives preserved from the work of the Šechtl & Voseček Studios started in April 2004. The goal is to catalogue the whole archive and to make it available in this museum and on the Internet. We are trying to make the highest possible quality scans to avoid the need to re-scan negatives.

We began work on the archive of glass plate negatives, containing the oldest photographs. In three years, we have digitized 8,000 negatives, out of an estimated total of 10,000 –13,000 negatives.

We only began exploring the 35 mm films left by Josef Jindřich Šechtl in 2005, because the collection was thought to contain only photographs of “old men”, from vacations in Yugoslavia, and at the spa in Jáchymov. We hoped that somewhere in all the rolls of film we had, we might find some interesting additions to our archive of glass plate negatives. Further motivation came from the recommendation we received from Kodak, to safely destroy the old nitrate films because of their chemical instability, and the slowly increasing likelihood of an explosion. Luckily our archive is in a relatively low state of deterioration, and thus we decided to fully digitize it. We were really surprised by the number of photo-essays we found, and also by the quality of the individual photographs, and by how well the pictures in the archive documented the times in which they were taken.

Digitization was done on a high quality Minolta 5400 film scanner with high resolution, 5400 DPI (40 megapixels). It has thus been possible to reproduce here almost all the photographs in the archive, in representative quality. Overall we have digitized about 300 films, comprising some 8,000 photographs.

You are welcome to explore our whole archive, either on the computer in our museum, or on the internet.

Josef Jindřich Šechtl

Josef Jindřich Šechtl (also spelled as Josef Jindrich Sechtl or Josef Schächtl) was born in Tábor on as the second of three children. His father, Ignác Šechtl, had opened his photographic studio in Tábor in 1876, and thus Josef Jindřich was influenced by photography from his childhood.

After finishing lower high school in Tábor, Josef Jindřich was particularly interested in chemigraphy (a method of printing photographs). At the age of 14 he started working as a trainee in the polygraphic factory of Jan Vilím in Prague. Later he changed jobs to work as a photographer in the studio of František Krátký in Kolín. His certificate of a completed apprenticeship, written in 1906 by his father, also certifies his studies in the Šechtl & Voseček studios in the period 1892 – 1895. At 22, after serving in the army (1898 – 1899), he started work in the affiliated Šechtl & Voseček studio in Czernovice, at Bukovina.

Since the photographs from the Šechtl & Voseček studio are not usually signed by the particular photographer, it is not clear which photographs taken during 1897 – 1911 were taken by Josef Jindřich or Ignác Šechtl. Josef Jindřich’s influence on the work of the studio is however apparent. Soon after the start of his career, the studio started to publish large photo essays on important events, and produced postcards signed Šechtl & Voseček. The earliest of these photo essays — such as the Sokol gymnastic festival (Slet), or the arrival of Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph I — contained about twenty photographs each. But the essays quickly grew larger, and the Regional Exhibition in Tábor in 1902 was recorded in over 100 photographs.

The main source of income for the studio however remained its studio work, in which Josef Jindřich excelled: despite the provincial location of the studio, his works were comparable with those of the best Czech portrait studios. His work is influenced by photographic pictorialism. His photographs express the personality of his subjects, often with a gentle sense of humor.

Josef Jindřich became a partner in the Šechtl & Voseček studio in 1904 and took complete control in 1911 after the death of his father. Under his lead the studio prospered, and in 1906 he opened an affiliated studio in Pelhřimov, while the studio also participated in the Austrian Exhibition in London. In 1907, a new and modern studio was built on the main street of Tábor.

The photographic work of Josef Jindřich was very much influenced by Anna Stocká, whom he married in 1911. Anna loved art, and thanks to her charm the family befriended several artists living in Tábor, in particular the sculptor Jan Vítězslav Dušek. In 1912 Josef Jindřich and Anna’s daughter Ludmila was born, and all seemed well. Josef Jindřich didn’t serve in the army during World War I, and thus had a chance to record life in Tábor during this period, including the fire that significantly damaged the Tábor studio in 1917. He recorded the fire in a unique photo-essay, with several snapshots made on small-format sheet film, and for a record, a “reconstructed scene” made afterwards as an exact reconstruction of one of the snapshots, on a 13×18 cm glass plate negative.

Much more disastrous for his life than the fire was the death of Anna in 1925 just six months after, and precipitated by, the birth of their son, Josef Ferdinand Ignác. His second marriage, to teacher Božena Bulínová, in 1926, wasn’t as happy; and Josef Jindřich began to concentrate more on work in the studio and less on family life.

In 1928 Josef Jindřich bought a Leica camera and started recording life on 35 mm film. As the Leica camera had only gone into production in 1925, he thus became a pioneer of Leica photography in the Czech lands.

During the life of Josef Jindřich, photography changed from a job that could be taken up and practised fairly freely to a regulated craft: first for portrait photography in 1911, and later in 1926 it was declared a full-scale craft, requiring apprenticeship and a permit to practice. In 1948, the new communist government socialized all services, including photographic studios. The Šechtl & Voseček studio was turned into a syndicate and nationalized in 1951 and, as a former tradesman, Josef Jindřich Šechtl was granted a small pension (200 Kčs per month).

Josef Jindřich died in Tábor on , aged 76 years.

Credits

The exhibition consists of 178 prints, from original negatives by Josef Jindřich Šechtl dated 1928 – 1954, and digitized using Minolta 5400 scanner. The exhibition occupies two floors in our Museum, U Lípy House. The exhibition was prepared by:

- Petr Chuchvalec, Martin Salay, Zbyněk Suchomel, Filip Zelený

- who by their expertise, improved the quality of the captions. Milan Fara prepared the presentation on Leica cameras.

- Jan Hubička, Marie Šechtlová and Eva Hubičková

- cooperated in digitizing the archive, and preparing photographs, captions and posters.

- Jan Kratochvíl, Eleanor Schlee and John Titchener

- translated texts to English, and significantly improved the quality of the captions and posters.

- Škrla Family

- provided a home for the exhibition.

- Jakub Troják

- prepared typography of posters, captions and invitation cards.

Photographs were printed on inkjet printers using Epson Stylus Pro 4800 by MS Microsun, and Epson Stylus Pro 9800 by Petr Šálek. We would like to thank our printer for his promptness, and his very competitive prices.

We also gratefully acknowledge the support we have received from the Town of Tábor, and the South Bohemian Region.