The beard in history, or the history of the beard…

Throughout human history, people have changed their surroundings and their appearance, to suit their needs, and to express their image. Dress, jewellery, and adornments have all been subject to fashion and fashion trends; and so have hairstyles and whiskers. The beard (in all its various forms) has expressed everything from religious belief, to political classification, to one’s position in society. In many different ways, the beard, or its absence, has been used to proclaim the manhood and physical strength of its wearer.

In ancient Egypt, beards were the norm for all men, but for the Pharaoh, his carefully cultivated beard was in fact a symbol of his power and authority. Very complicated and careful hair styles (including beards) can be seen adorning statues and embossments of gods, kings, soldiers and other notables from Mesopotamia and Persia. It is obvious that any Assyrian, Babylonian or Persian “dandy”, or high-positioned notable, was socially unacceptable without a carefully cultivated beard. Such a beard positioned its owner within the higher social classes, and clearly differentiated him from ordinary citizens. The same applied in ancient Palestine and India.

The ancient Greeks inherited these cultural values. Even here the beard played an important social role, and the idea of a beardless Greek philosopher or dramatist is for many of us unthinkable, even though the reality was often different. The beard was part of mythology. The king of the Greek pantheon, Zeus, and his brother Poseidon, the god of the sea, are always pictured with beards. On the other hand, Zeus’ son, the god Apollo, is always portrayed as a beardless young man. Different forms of beard became an idiom of Greek culture and fashion. Preserved pictures tell us of many different fashions of hair and beard styles. Greek soldiers – the heavily armoured hoplites – became famous for the care they took in their appearance before a battle, especially regarding their beards.

Ancient Rome didn‘t follow this Greek tradition, and the beard was considered to be more or less barbarian. A strong advocate of shaving was Scipio Africanus (who defeated Hannibal), and because of him, the shaven face became a symbol of Roman superiority over the rest of the world. All Roman emperors had shaven faces until Hadrian, who admired all things Greek and who, wishing to imitate Greek culture, introduced the beard to Roman high society. Admiration of Greek culture and stoic philosophy (in the modern world, our image of the stoic philosopher is of the bearded ascetic) culminated during the life of Emperor Julian Apostata (332–363). Julian had rejected Christianity, and wanted to restore the old pagan cults. Because of his ascetic lifestyle, he came into conflict with the profligate elite of society in Antioch, Asia Minor. He recorded this conflict in his text “Misopogon” (“Beard-hater”) where, in an ironic way, he criticised both himself and what he saw as being the profligacy and intolerance of Roman society.

The end of the ancient world brought a decline in the care of hair and beards. The newly arriving barbarians didn‘t bring any new ideas, and slowly accepted the ways of the former inhabitants. By the Middle Ages, people knew more about care of hair and beard, but, with a few exceptions, this time saw a preference for shaven faces. Some renaissance of the beard was brought by the religious Reformation. Protestant leaders with beards (following the example of the Old Law prophets) helped to popularise wild beards. Also influential was the Thirty Years War, when the cultivated beard was an almost essential part of the image of army heroes, and adventurers travelling across Europe. But these influences gradually waned, which was probably the reason why male faces in 18th century Europe were generally shaven. An exception however was the great popularity of Hussar or Grenadier moustaches in contemporary armies, when soldiers not having this manly decoration were required to try to draw it on with coal.

The end of the 18th century was the end of the old world, with its shaved faces. Revolutions brought in the romantic bearded appearance. Europe saw a resurgence of the beard after the Napoleonic Wars, culminating in the revolutionary year of 1848. Goatees and moustaches adorned the revolutionaries, and also the new emperor, Franz Josef I. Soon, many European crowned heads (for example, French Emperor Napoleon III, Russian Tsar Alexander III and Prussian King Friedrich III) were displaying magnificent beards. Monarchs led by example, and thus the second half of the 19th century became the “golden era” for beards. However, all of that was ended by the First World War. The beard didn‘t fit the battlefield (mainly because of newly developed chemical weapons and the need to wear gasmasks), and the golden time of the beard ended.

The post war era was dominated by different ideals (mostly from movie films), and introduced a lot of freedom in hair and beard care. Wild beards became less common, and the world is again controlled by the fashion of shaven faces. Wars and turmoil are promoting it again today.

— Libor Jůn

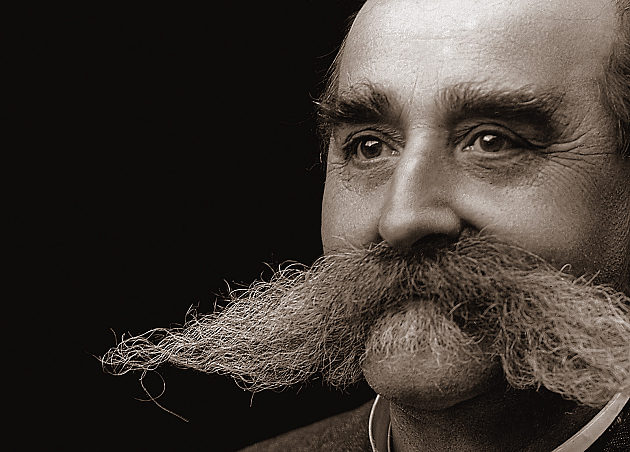

Photographs for text by Libor Jůn was selected from the digital archive of Šechtl & Voseček sutdios. They are an example of portrait work of three generations of Šechtl family—Ignác Schächtl, who later changed his name to Šechtl (1840–1911), Josef Jindřich Šechtl (1877–1954) and Marie Šechtlová (1928–2008). Portraits were mostly taken in Tábor studio, and are dated to years 1858–1966. Unless otherwise specified, all photographs have been prepared from original glass plate negatives.

From the work of the Šechtl & Voseček studios, a large archive of negatives has been preserved. Since 2004, we have worked on their digitization. Of the 18214 photographs that have been digitized up till July 8th 2007, 2560 are portraits. Sadly, the majority of our photographs are not identified. We would be very grateful for any additional information about any of the photographs in our archive.

Photographs are available on the Internet, at address https://sechtl-vosecek.ucw.cz/en/ , and in the Šechtl & Voseček Museum of Photography (in U Lípy House, Mikuláše z Husi Square, Tábor).

Šechtl and Hubička family

On the photos: Mr. Bůček, Žirovnice, 1909